Mary Armstrong: A Freedwoman

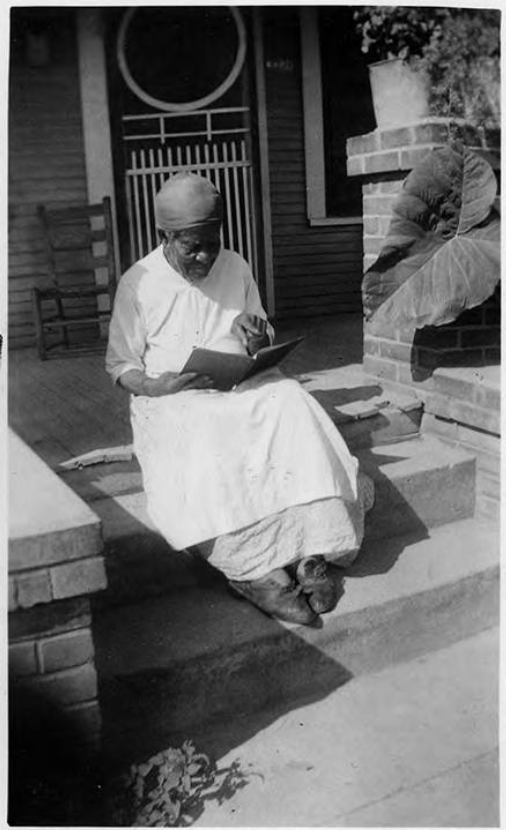

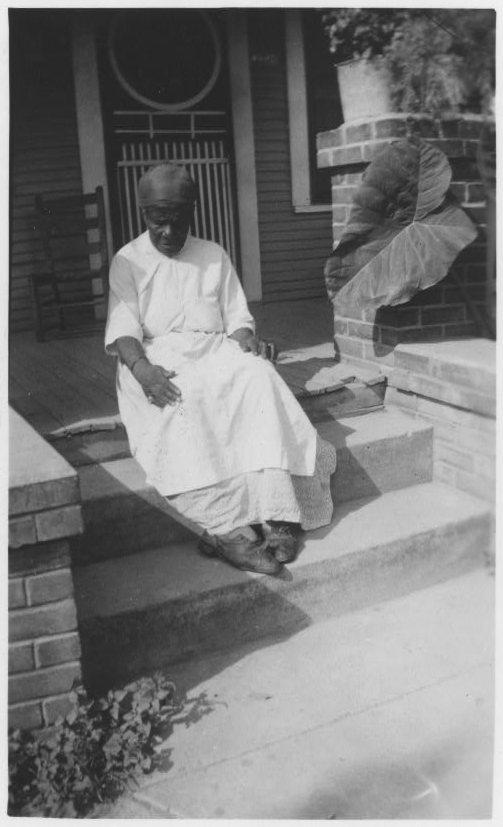

Mary Armstrong, a formerly enslaved woman, was interviewed by the Works Projects Administration (WPA) at her Houston residence on August 8, 1937.

If you’re interested in reading Mary’s interview in detail, you can find it here.

Warning: There is some intense violence and cruelty in this post.

Mary’s recollection was incredibly difficult to read but I did not “soften” or remove any of it from this post. The institution of chattel slavery, and its cruelties, should not be sugarcoated and these stories deserve to be told in entirety.

Plantation Life

Mary was born on June 2, 1847 in St. Louis, Missouri plantation to enslaved parents, Sam Adams and Silby [Sylvie]. Mary, her younger sister, and her mother belonged to plantation owners William and Polly [Pauline] Cleveland. Mary’s father, Sam, belonged to William Adams, a slave trader who lived on a connected plantation.

“But that old Polly [Pauline] was mean like her husban’, old Cleveland, till she die, and I hopes they is burnin’ in torment now.”

Mary Armstrong, August 8, 1937

Cruelty Beyond Measure

During her interview, Mary vividly recollected the cruelty William and Polly [Pauline] Cleveland doled out to their enslaved subordinates. The most disturbing of these memories was the brutal murder of her 9-month old sister at the hands of Polly Cleveland.

Polly, apparently enraged by the baby’s crying, removed her diaper and beat her to death.

She come and took the diaper offen my little sister and whipped till the blood jes’ ran — jes’ ’cause she cry like all babies do, and it kilt my sister.

Mary Armstrong, August 8, 1937

Although Mary was 91 at the time of the interview, the memories of her baby sister’s death remained painfully clear.

While it may seem that Pauline took the cake for cruelty, she was not to be outmatched by her husband. William Cleveland’s moral compass regularly malfunctioned both on and off of his farm. The most striking example of this was his tendency to rub salt and pepper on the skin of his enslaved men prior to whipping them.

Mary told interviewers that he simply wanted to, “season him up” before the beating.

Full-time enslaver, part-time scammer

Cleveland would often take out loans against his own slaves and then transport them to the South for sale. When it came time for the lender to collect, Cleveland would tell him that the slave escaped and usually did not have to repay the loan.

When he did follow through on his sales, Master Cleveland did not acknowledge enslaved family units. He always sold mothers separately from fathers, and both separately from their children. Eventually, Mary’s own parents were also sold, though she would later reunite with her Mother after the Civil War.

An Eye for an Eye

“Well, I guess mamma has larnt her lesson at last.”

Mary Armstrong on August 8, 1937, recollecting the words of her former mistress, Olivia Cleveland Adams

Olivia Cleveland Adams was the daughter of William and Polly Cleveland, and the wife of William Adams. She was, according to Mary, the complete opposite of her parents as she was loving, kind, and adored by blacks and whites alike. Olivia took a liking to Mary and William Adams purchased Mary from his in-laws for $2,500.

Mary describes Olivia’s temperament while sharing a story from when she was 10 years old. Polly Cleveland visited her daughter’s home and attempted to whip Mary in the yard. Mary picked up a rock roughly half the size of a grown man’s fist and busted her eye open. Mary later confessed to Olivia who responded that her mother had finally learned her lesson.

The Adams Family: A Light Within the Darkness

“…But Miss Olivia say, ‘I’d wade in blood as deep as Hell ‘fore I’d let you have Mary.’ That’s jes’ the very words she told ’em.”

Mary Armstrong , August 8, 1937

Mary spent the rest of her enslavement in the Adams family home. Aside from the sadness of missing her mother, her quality of life improved greatly. She assisted the household by performing domestic duties such as nursing infants and spinning thread. Her lighter workload provided plenty of free time, so she filled these gaps by learning how to dance. She became so skilled at dancing that Olivia would request to see her waltz around the room.

At one point, Polly Cleveland attempted to purchase Mary back from her daughter. Olivia outright refused claiming she’d rather “wade through a bloody Hell,” than lose her beloved Mary. Polly was also not allowed to lay a finger on Mary, or any of their 500 enslaved persons, while visiting their property.

Olivia and William seemed to genuinely care for Mary, a fact that she reiterated several times during the interview. She referred to William as, “Mr. Will” in front of company, rather than “master.” In private, she referred to the Adams’ as “pappy” and “mammy.”

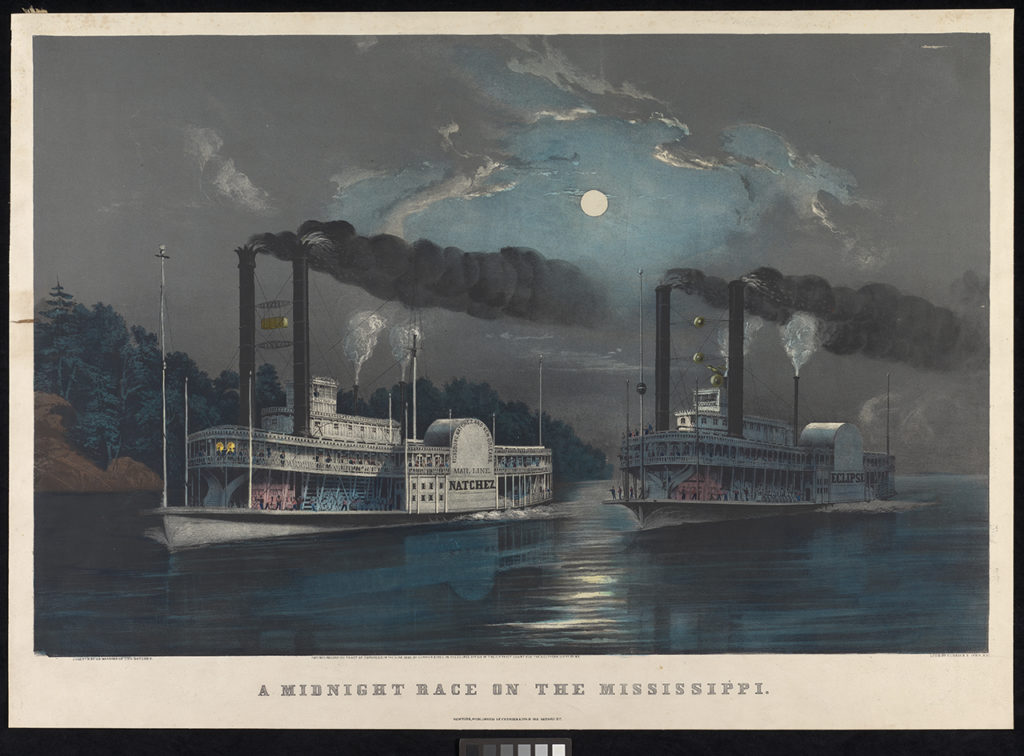

On one occasion, William took Mary on a spontaneous trip to spectate a late-night steamboat race along the Mississippi River. Mary excitedly recounted the Natchez and The Eclipse racing each other neck during the event. At the end, the Natchez burned bacon grease to gain an advantage.

“A Midnight Race on the Mississippi” / Frances Flora Bond Palmer / 1860

Freedom and Family

“I looks ’round Houston, but not long. It sho’ was a dumpy little place then and I gets the stagecoach to Austin.”

Mary Armstrong, August 8, 1937

Mary lived with the Adams family until 1863, when William Adams emancipated his plantation upon receiving word of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. William Adams gave her official, sealed documents declaring her freedom and lectured her on the importance of what exactly to expect in the Deep South. He warned her that there were still slave plantations in the South and to make sure she minded White people in order to secure her safety. In the event that she was taken by a slave trader, she was to display her documents, but only when she was upon the auction block. William assured her that this was the best way to remain safe and avoid potential violence.

Olivia and William Adams gave Mary money, clothes, and plenty of food for her river-bound journey to Houston, Texas. Olivia was particularly sad about her departure and told her to be careful as it was “rough in Texas.”

After several boat trips and a stagecoach journey, Mary arrived in Austin, Texas. Upon her arrival she was immediately “greeted” by traders and taken to an auction block. She followed the instructions William gave her and was quickly released.

The slave trader, Charley [Charlie/Charles] Crosby, was a legislator and decent enough man for someone who facilitated the purchase of human beings. He told Mary of a refugee camp in Wharton County for the formerly enslaved and invited her to stay on his property. A slave owner himself, he allowed Mary to live in his slave cabins and hired her for work. She worked for Crosby until the end of the war and then headed to Wharton County in search of her mother.

Mary located her mother, Silby [Sylvie], in Wharton Country and they lived together until Mary’s marriage to John Armstrong in 1871. After the marriage, the three of them moved to Houston where Mary worked as a nurse for a Dr. Rellaford during the Yellow Fever pandemic.

Houston Homes

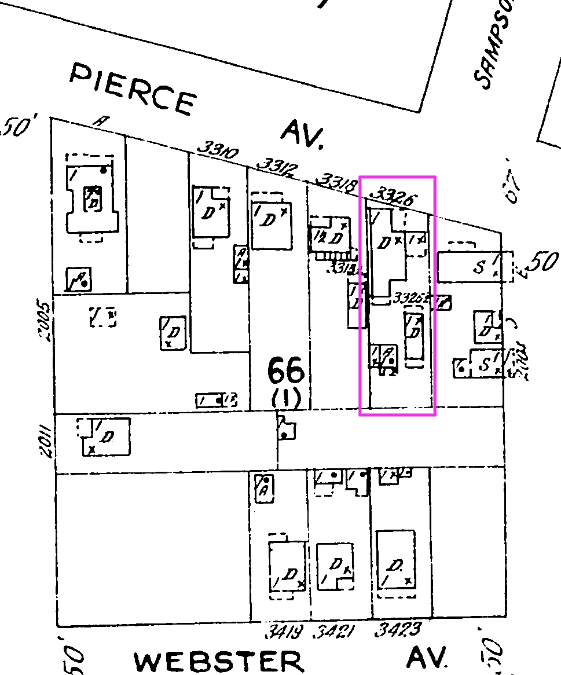

Mary’s interview took place at 3326 Pierce Street:

Mary was 91 at the time of her August 8, 1937 interview and died on September 23, 1937 from “senility,” as per her death certificate.

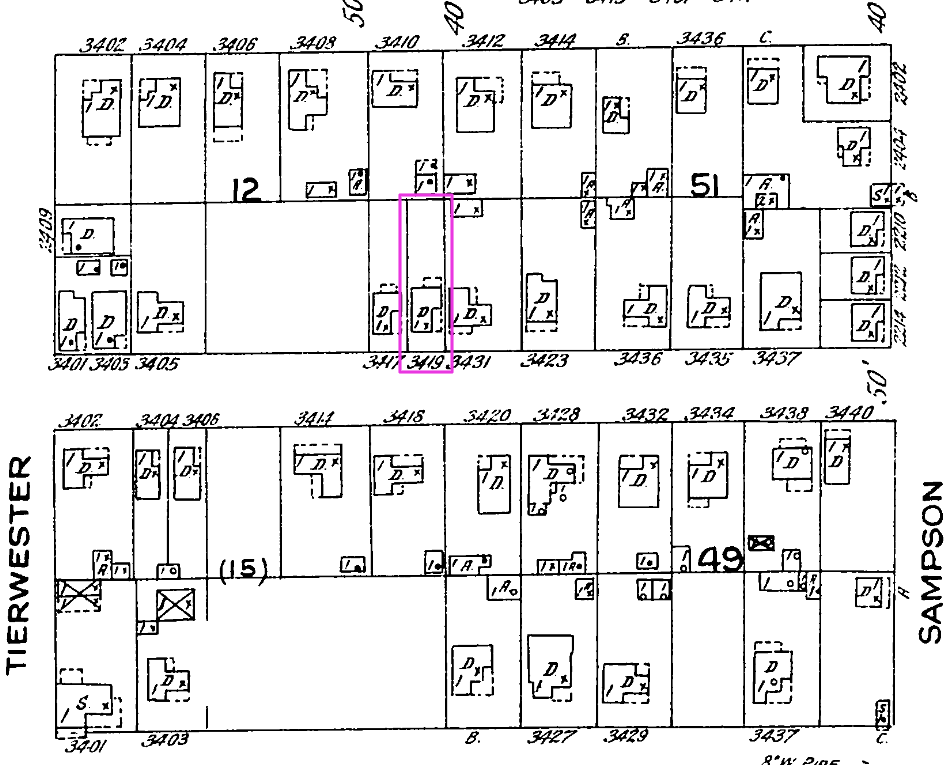

She must have fallen ill rather quickly, which may have resulted in a location change. Mary’s residence at the time of her death was 3419 Bremond Street, which was 3 blocks away from her previous home.

There is much more to Mary’s story and I omitted quite a bit for length’s sake. You read Mary Armstrong’s narrative in full here.